Destructive lanternfly could affect County’s vineyards and tree canopy

Administrator | Aug 09, 2023 | Comments 0

By Sharon Harrison

By Sharon Harrison

As colourful and pretty as it looks, the distinctive adult spotted lanternfly is ugly in its mission to decimate certain plants and trees.

When it arrives in Canada, as it is expected to do at anytime, its impact could be devastating, particularly to the agricultural industry as it pertains to grapes, hops and fruit trees, basically making grape-producing regions vulnerable.

With the loss of countless ash trees across the Prince Edward County landscape, destroyed without mercy by the emerald ash borer in recent years, the thought of another potential insect making its way to Canada, to Ontario, and to Prince Edward County, isn’t the news anyone wanted to hear.

Last week the public was welcomed to a free workshop at the Bloomfield Town Hall, hosted by the not-for-profit organization, Invasive Species Centre, about the latest invasive species to potentially settle on our shores, the spotted lanternfly.

Emily Posteraro, program development coordinator with the Sault Ste Marie-based Invasive Species Centre

The informative, detailed, interactive talk given by Emily Posteraro, program development coordinator with the Sault Ste Marie-based Invasive Species Centre, addressed what the spotted lanternfly is, where it is, and what it might do if it reaches the County.

The Invasive Species Centre’s work is to prevent the introduction and spread of invasive species that harm Canada’s environment, economy and society.

“I wouldn’t say for certain there is no spotted lanternfly here; it just hasn’t been found, that we know of,” said Posteraro.

At the well-attended public meeting, some of whom were members of the local grape-growing and wine industry, Posteraro explained how to spot the spotted lanternfly (generally referred to as SLF), but most importantly how it spreads, and how to stop its spread.

She also covered its impacts, how to prevent it, and the importance of early detection and rapid response, as well as reporting sightings, as she highlighted monitoring efforts currently on-going in Ontario.

She explained the criteria for declaring a plant, insect or animal “invasive” where it was noted other invasive species locally include zebra mussels, emerald ash borer, long-horned beetle, spongy moth, dog strangling vine, and buckthorn as some examples.

The SLF belongs to the planthopper group of insects and as yet does not exist in Canada it is believed by those experts (provincial government agencies) tracking its movements. However, it is in the United States, in New York state, in Buffalo, just across the US border and is too close for comfort, and very likely to reach Canada, and southern Ontario, sooner than later.

The insect, declared an invasive species here, found its way to North America from its native land China, Vietnam and Taiwan where its preferred host plant here is the tree of heaven (also an invasive species). The SLF is also invasive in other countries, such as South Korea, Japan and more specifically north-eastern United States where it was first detected in 2014, in Pennsylvania.

“That’s why it’s become a threat to Canada because it’s spreading close to the border, and this is especially a threat to vineyards, but also orchards, forests and parks,” explained Posteraro.

It was noted the SLF is in 14 US states now, including New York, Michigan, New Jersey and West Virginia among them, but it has not yet reached California who are in a preventative stage.

“This is where climate change comes into the mix, you can’t really rely on cold Canadian winters anymore to kill off insects that otherwise wouldn’t have been able to survive and overwinter here, as the winters are getting milder.”

The SLFs preferred host plant is tree of heaven, also an invasive species, which they like to feed on it, but also lay their eggs on it. A tree than has been here centuries according to Posteraro, she emphasized that while tree of heaven if the preferred host plant, it is not necessarily the obligate plant host for SLF.

“It was introduced in North America as an ornamental in the 18th century and now it’s quite wide-spread; in Toronto it’s on every block, it’s quite common and is probably the fastest growing tree in North America, and it really thrives in partly-disturbed areas,” she said.

“There is a bit of a myth that it needs tree of heaven to survive, but that’s actually not true, even though it is preferable.”

“The SLF can have a devastating ecological, economic and social impact, if and when it gets here, and so it’s really important to us to enable early detection and rapid response.”

She spoke to how the public can learn to recognize and report SLF if and when it arrives.

Posteraro said what they know comes from one study in Pennsylvania in 2014 where it was first detected, as they have been dealing with it the longest. She explained that while the outlined economic scenarios in some US states were bleak, she said the same outcome won’t necessarily happen here.

“It depends on how bad the spread gets, and what we do to contain it, different measures cost differently, but we do have obviously significant wine industry at stake here and it really is the grape vines that SLFs are incurring a lot of damage to and what we are worried about here, because basically, what it does is weakens and kills plants.”

It was pointed out by Posteraro that the Niagara region was quite vulnerable too because it is on the US border.

“Because of a lot of travel back and forth, and, of course, it is a high production of grapes, tender fruits and hops, but SLF could be transported anywhere in Canada,” she said. “So, Prince Edward County, it could definitely end up here with trucks, etc., and there is high vulnerability here to the vineyards.”

She pointed out that an infestation of more than 100 adult SLF was found in Erie County in New York state last fall, on the border of Buffalo.

“We are thinking it is only a matter of time before something gets here. We have had dead SLFs detected in produce. It’s right on our doorstep, so it could very well end up here soon and as far as we know, it’s not here yet.”

Posteraro spoke to how plants and trees are dealing with a lot of environmental stressors right now.

“SLF is an environmental stressor, so it’s just going to be another additional pressure on our habitats and our eco-systems, when we are already dealing with a lot.”

She pointed out that while SLF is considered an agricultural pest, because it usually relates to grape vines and vineyards, she noted that it could have widespread ecological impacts because it has such a broad range of possible plant feeding hosts, including hardwood trees.

While tree of heaven is the primary host for SLF (tree of heaven is similar looking to the native black walnut tree, with some subtle differences), the insect also targets grape vines, fruit trees, hop vines, and trees (including maples, oaks and black walnut) .

She said it will also affect wild grapes, of which they are a lot in the County.

“It has been documented that there are over 100 different species [SLF feeds on]; it is very possible that it could encounter and feed on more plants than currently documented as it spreads.”

Examples of some of the host plants SLF feeds on include oak, black walnut, maple, willow and poplar, although it seems to have a lower preference for conifers. “Basically, it will feed on anything,” she said.

Research has found that it seems to be a little less common n areas of undisturbed contiguous tracts of forest, and is more prevalent in areas of more human populated areas, or edge habitats, “so it’s important to keep our forests intact”.

Posteraro described how the insect damages a plant or tree by feeding on the plant phloem (what carries the sugars throughout the plant) which causes the plant stress because it needs the sugars, even if it doesn’t quite cause their mortality.

“Basically it’s weakening the plant and is making it less resilient to other insects and pathogens, and stressors caused to climate change,” she said. “What they do is feed, then excrete a waste in the form of honeydew (a sugary excrement), and what that does is form sticky pads at the base of the plant and that fosters mold growth.”

She said this is bad for the plant and will reduce its ability to photosynthesise, and also block growth for understory plants.

Addressing a question about whether the SLF has any known predators, while it has been documented that birds have fed on the SLF, Posteraro said it is not enough to keep the SLF populations low as they have continued to grow and spread.

“The big thing that they are doing in terms of damage is killing those grapevines; they are definitely not being controlled by any natural predators.”

SLF don’t seem fussy on what they eat and will eat new shoots as well as older growth, and will traverse the full tree, getting right to the very top.

“They will start feeding low, and then they will climb high up into the tree, basically the whole plant of any age, and they penetrate the bark and are feeding on the sugars; they climb pretty high,” she said.

Tree saplings are more vulnerable to negative impacts, said Posteraro, and would be more likely to be killed, whereas a SLF is unlikely to kill a full-grown, healthy tree.

When it comes to SLF, prevention is key, and is also the most cost-effective phase of managing the destruction of SLF.

“It makes a lot of sense to invest in prevention; once it actually arrives and you put money into eradicating it, and then it spreads and you are past that point, once you are getting to just long-term management, it is very expensive.”

She also elaborated on the importance of early detection and rapid response (EDRR) and how it is a key tenant of invasive species management ,saying, “when prevention isn’t possible, when SLF gets here anyway, EDRR is our next best thing, so the emphasis is on detecting and reporting invasive species, especially through community science (self-reporting via apps, websites, etc. by the public), as the earlier an invasive species is detected, the more likely it is to eradicate it or keep it contained.”

She noted that there has been recent past success with EDRR, noting the Asian long-horned beetle was deemed eradicated finally in Canada in 2020.

Speaking to the basics of the biology of the SLF, it is part of a group of insects known as planthoppers; it is not a fly or a moth. They adults do fly, where their tendency is to swarm in large congregations, but Posteraro noted SLF do not bite or sting people.

While the adults to do not overwinter or survive the cold temperatures in this area, the eggs, which are laid in the fall and winter overwinter successfully, where they can survive to at least -20 degrees Celsius.

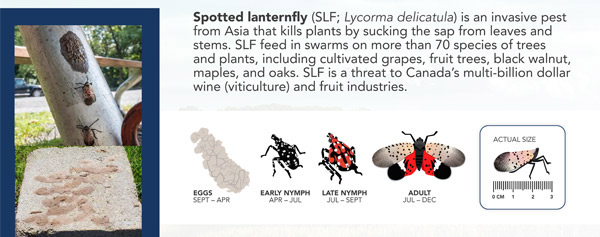

The eggs which hatch in May/June turn into early nymphs and are still very small at about one centimetre in length, and by July the nymphs enter the next phase of their life-cycle adopting a red colouration as they become adults (growing to 2.5 cm) when their activity increases in September/October and swarming begins as they begin to breed.

SLF only have one lifecycle and once they lay their eggs, they die.

Dark streaks on the bark of a tree is one of the signs that SLF are present, also sap flowing down the trunk, as well as the presence of sooty-coloured mould, also increased wasp activity may be an indication of their presence.

The egg masses first appear shiny but become dull and cracked over winter appearing as a smear of mud on a tree trunk or bark (resembling the skin of a cantaloupe), but the SLF will lay their eggs on almost anything, including any smooth hard surface where they may go unnoticed, for example, on vehicles, crates, firewood, patio furniture, stoneware, etc.

Posteraro noted that when eggs are laid on vehicles or campers, or commercial truck traffic, that is when the SLF easy travels from place-to-place (and country-to-country), therefore spreading the invasive insect.

In conclusion, Posteraro said the public should take the time to spot SLF, snap it, catch it and report it.

Reporting any potential sightings of the SLF should be first done with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, where she suggests also making the Invasive Species Centre aware, as well as recording it on eddmaps.org (which is free).

Any report of SLF (or egg masses) -however uncertain the identity- should contain as much information as possible, with an address of the sighting, a description, a photo and collected specimen (ideally kept in a container in a freezer).

“We would rather get a report that is wrong, rather than not get a report of a SLF when someone saw it,” Posteraro said.

She also encourages reporting sightings of the tree of heaven too on eddmaps, given it is an invasive species and the favoured host plant for the SLF.

“That will show us where tree of heaven is distributed and that will give us a better idea of where SLF could establish,” she said.

Emphasising that if a member of the public reports a tree of heaven, it will not trigger a follow-up inspection or removal of a tree on private property, “reporting it allows us only to map it”.

Given that tree of heaven is confusingly similar in appearance to the black walnut tree, and staghorn sumac, Posteraro suggests the best way to identify tree of heaven is to crush the leaves and if it has a pungent smell of burnt peanuts, it’s tree of heaven.

She noted the on-going monitoring efforts by the Ontario government who have installed bug barrier traps on host trees which have been deployed in southern Ontario at hotel sites, wineries, campgrounds, rest stops, etc.

“SLF is an invasive agricultural pest and a plant stressor that is spreading rapidly in the US, with infestations as close as Buffalo, New York making this quite urgent,” said Posteraro. “Grape-producing regions in Canada, in southern Ontario included, are of course vulnerable, but there is also a good opportunity for prevention and for early detection and rapid response.“

She encourages everyone to learn to recognize SLF in all life stages, including the egg masses.

She also encourages anyone making a car trip to infected areas of the US, such as Pennsylvania or New York, to check their vehicles upon return to Canada for eggs, or suggests a high-pressure car wash once in Canada will be helpful since the eggs can be hard to spot.

While the SLF tends to pose less damage to orchards, it does like to feed on apples, peaches, plums, cherries, although she said the SLF doesn’t seem to kill those trees or do much damage.

She added that SLF feeds on stems and trunks, and is not eating the leaves or the fruit, but are feeding on the stems of the plants.

Posteraro said SLF won’t kill most plants, but their presence will be a stressor for some plants, “it will kill saplings and grapevines, big time they can kill, but they won’t wipe out an area and move on, as they always find something to eat as they are very generalist feeders”.

“A big reason we are worried about it is because of the grapevines; in a worst case scenario in Pennsylvania there are vineyards that have been completely wiped-out by an SLF infestation.”

“On the positive side, it is not here yet; we are in the preventive stage and this is one of the key strategic regions to engage stakeholders and the public in preventative efforts, but we do need to be prepared now.”

Click here to visit the Invasive Species Centre website

Filed Under: Local News

About the Author: