Local native and settler history opens library’s Indigenous history month programs

Administrator | Jun 21, 2021 | Comments 1

By Sharon Harrison

Celebrating National Indigenous History Month, the Prince Edward County Public Library is hosting several programs for adults and children.

With Monday, June 21 is National Indigenous Peoples Day, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau noted that while it is a time to celebrate Indigenous peoples from coast-to-coast, “it is also an opportunity to acknowledge that there is much more work to do on the important journey to reconciliation. The recent tragic findings of remains near the former Kamloops Residential School serve as a stark reminder of the systemic oppression, inequalities, and discrimination that Indigenous peoples have endured over the past years, decades and centuries, and the injustices and challenges they continue to face today.”

Opening the library series, local archivist Amanda Hill provided a glimpse Friday into the relationship between Indigenous peoples and settlers in the region as part of the National Indigenous History Month programming.

Hosted by the Prince Edward County Public Library, the virtual presentation “Natives and Settlers: The View from the Archives” referenced written records and physical artifacts from museums and archives around the world.

Amanda Hill

Arriving in Prince Edward County in 2007, Amanda Hill trained as an archivist in the England in the 1990s and was employed at Canterbury Cathedral Archives. She has worked for the Town of Deseronto Archives Association of Ontario. In 2015, she became the archivist for the Community Archives of Belleville and Hastings County.

“When I arrived here, I was so caught up in my own immigration journey, I hadn’t given any thought to the historic circumstances that enabled me to take advantage of that opportunity,” said Hill. “I now appreciate these lands support Huron-Wendat, Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee before the arrival of Europeans. I think it’s important for all people who live here to understand more about how we got to where we are today.”

She spoke to the shared history of native people and settlers in the Bay of Quinte region specific to the late 1700s, which Hill describes as a time of wars and great change in this part of the world.

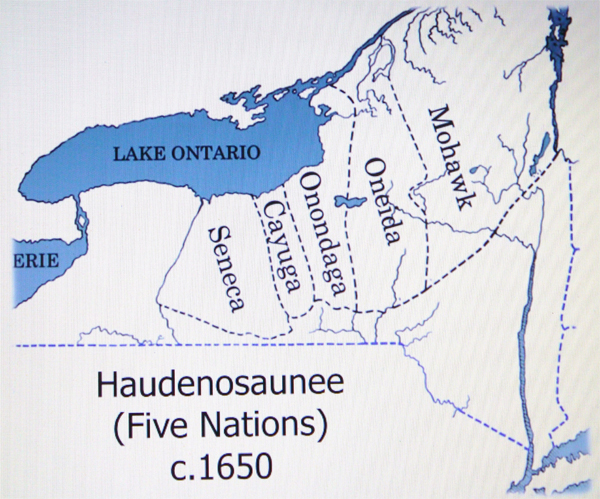

Hill noted the location of the Haudenosaunee people, or the Five Nations, were known by the French in 1650 as the Iroquois.

“By this time, the Five Nations had been members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy for at least 200 years,” explained Hill.

The confederacy is governed by a grand council of 50 chiefs, or sachems, representing each clan of the nations.

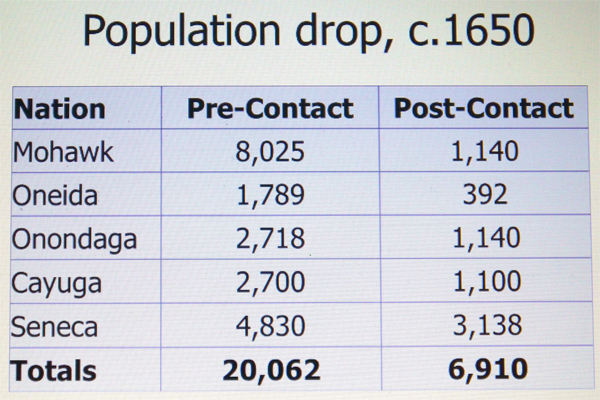

“At this stage, the Indigenous population were being exposed to European diseases to which they had no immunity,” Hill said. “A study into the archeological remains of the Haudenosaunee settlement suggests two-thirds of the native population died in the years immediately following European contact.”

“The pandemic we are dealing with today is disruptive enough, but these numbers show just how devastating the diseases of the settlers were for the Indigenous population as the epidemic spread westward.”

Hill describes how the Mohawk people were the worst affected, probably because their region was the closest to the European settlements.

Hill describes how the Mohawk people were the worst affected, probably because their region was the closest to the European settlements.

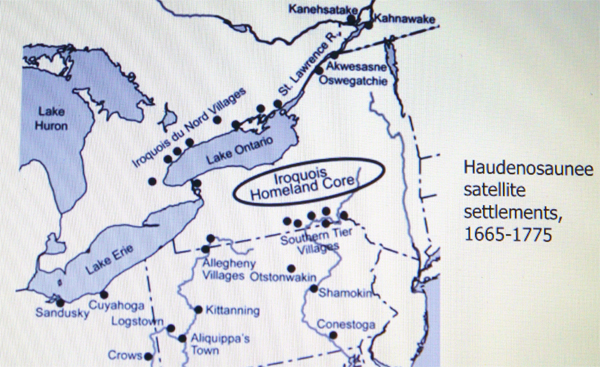

“Despite this loss of their own population, the Haudenosaunee were able to expand their area of movements in the next century.”

Maps show the locations of Haudenosaunee settlements beyond their 1650 homeland, including villages on the northern side of Lake Ontario. The villages along the St. Lawrence River were created by the migration of Haudenosaunee converts to Catholicism, mostly Mohawk people.

The Haudenosaunee traded furs with the British in what is now the United States, and the French, in what is now Canada, and many of these external settlements were established in order to control the supply of furs from the north, explains Hill.

“The friction between the French to the north, and the British colonies to the south, put pressure on the Indigenous peoples to align themselves with one side or the other in the various wars that arose in the 17th and 18th centuries.”

By 1698, Hill explains how relations between the colonial province of New York and the Haudenosaunee had been delegated by the New York provincial government, to a body called the Albany Commissioners of Indian Affairs.

“This group was made up of fur traders and merchants of mostly Dutch descent who had close business connections with the Haudenosaunee.”

She notes how Peter Skylar served as commissioner for 20 years and was known for his knowledge of the Mohawk language.

“He instigated a diplomatic mission in the spring of 1710 when he accompanied four Indigenous chiefs on a visit to see Queen Anne in London and were treated as celebatories during their visit. Three of these men were Mohawks and one was a Mohican and they presented the Queen with wampum belts and requested military assistance against the French in Canada. They also suggested she could send Anglican missionaries to counter the influence of the French catholic priests.”

Queen Anne also authorized the construction of a fort in the Mohawk valley: Fort Hunter was built in 1712 and included a chapel.

“On April 10, 1712, Anne ordered that a silver flagon, a challis and a plate be delivered to each of her Indian chapels and those inscribed silver items still survive and are kept by the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte along with a later chalice given by Queen Elizabeth II in 1984.”

It was one of a series of gifts given over the years to commemorate the relationship between the

Haudenosaunee and the British crown.

The first missionary to the Haudenosaunee was a man called William Andrews who lived at Fort Hunter from 1712 to 1719. An object that survives from his time there is a translation of religious texts into Mohawk language.

“In the first half of the 18th century, the Haudenosaunee pursued a policy of new charity, supported by the Albany Commissioner of Indian affairs,” explains Hill. “This enabled them to continue to trade across the border with the Mohawks who had settled along the St. Lawrence and to them with the French settlers.”

Hill shares how the Albany commissioner was careful to share protocols of sharing gifts and resources with their native allies.

“During King George’s war (1744 to 1748), the Haudenosaunee continued to maintain their neutrality with support from New York merchant community until New York Governor George Clinton bypassed the Albany Commissioners and appointed William Johnson as a private agent with authority to deal with Six Nations and the funds to support his activities.”

Clinton wanted the Haudenosaunee to join the war on the British side in November 1746, the Albany Commissioners resigned and handed over their records to Johnson who now held the title of Colonel of the Six Nations.

William Johnson was an Irishman who became successful fur trader and general merchant. He was particularly associated with the Mohawk people and it was principally the Mohawks who responded to his call to arms in King George’s war.

“Johnson spent so much money that the New York assembly refused to pay his accounts and he resigned in 1751,” said Hill. “The Albany commissioners were reappointed in 1753, but a new threat of war against New France meant the British reverted to more direct control over Indigenous relations and they returned to William Johnson as their agent.”

After a modest military success over the French and the native allies of the battle of Lake George in 1755, he was appointed as sole agent and superintendent of Indians and their affairs in February 1756 and made a baronet.

“Some Haudenosaunee warriors fought on the British side towards the end of the seven years war and they helped Johnson take Fort Niagara in July 1759,” describes Hill. “About 700 warriors went with Johnson and the British Commander in Chief General Amherst to Montreal in the final campaign of the war.”

Hill says after the surrender of the French, Johnson was heavily involved in negotiating with the various Indigenous nations in the form of French territories.

“At this time, he was reporting to Jeffery Amherst the British Commander in Chief in North America,” she said. “Although he was happy to make use of the Indigenous population in these campaigns, Amherst was particularly unsympathetic to their situation. He disagreed with William Johnson over the necessity of continuing to supply native people with ammunition and other gifts and this lack of support became one of the direct causes of Pontiacs War in 1763 when Indigenous groups attacked colonial settlements and forts.”

Amherst wrote on August 10, 1763 that, ‘the Senecas with all the other nations on the lakes must be deemed our enemies and used as such, not as a generous enemy, but of all the vilest race of beings that ever infested the earth and whose riddance from it must be esteemed a meritorious act for the good of mankind’.

Hill noted that Amherst is also famous for his response at the Siege of Fort Pitt in the early summer of 1763.

“There is evidence in an account book held at the British Library that the people at the fort did indeed try to infect visiting natives with smallpox, although there is debate among historians whether this was Amherst’s fault or whether it would even have been effective.”

“It is safe to say that the relationship between colonial settlers and the Indigenous population reached a particularly low point in 1763,” Hill said.

In that year, Johnson moved into his new home at Johnson Hall which still stands in Johnstown, New York and is designated as a state historic site.

“I think it is interesting to see the stone block houses that Johnson build either side of the house, this is part home and part fort and very much speaks to the vulnerability of the settler population of New York at this time.”

On September 25, 1763, Johnson wrote to the Board of Trade in London with a summary of his understanding of the native population.

‘I know that many mistakes arise here from erroneous accounts formerly made of Indians, they have been represented as calling themselves subjects although they desire to be considered as allies and friends and such we may make them at reasonable expense and thereby occupy our outposts and carry on trading in safety, but until such measures be adopted, I am welcome there can be no reliance on a peace with them and that interest is the grand tie that will bind them to us, so their desire of plunder will induce them to commit hostilities whenever we neglect them.‘

Hill explains how in the next month, the royal proclamation was issued and included some clauses written in response to the unrest in North America, namely that, ‘the area west of the Appalachians was reserved for hunting lands for the several tribes or nations of Indians under royal protection, only the crown could buy indigenous lands, and unauthorized settlers would be removed from unpurchased lands’.

Shortly after the proclamation was issued, Jeffery Amherst was recalled to London and was replaced by General Thomas Gage who had been governor of Montreal.

“Gage was more willing to work with William Johnson than Amherst had been on negotiating peace with the disaffected Indigenous people,” Hill said. “On February 19, 1764, Johnson wrote to Gage recommending a treaty of peace be signed with them.”

In his letter, Hill says he talks about using forms which they take the more notice, noting that as natives, they did not use written language. ‘They must be frequently reminded of their promises since the neglect of the one will prove a breach of the other.’

This meeting has held in Niagara in the summer 1764 and is thought to be the most widely represented gathering of native people ever assembled.

The text of the proclamation was supplemented by the conference of the nations and reinforced with wampum belts.

“It reinforced the nation-to-nation relationship between the British and the First Nations,” Hill said. “This treaty extended this covenant change relationship between the British and the

Haudenosaunee to all of the First Nations represented at Niagara, over 24 of them.”

The hexagon shape in the belts represent the council fires at key locations across the Great Lakes.

By 1768, tensions in the American colonies were rising, and the American Revolution progressed over the next few years becoming war on Gage’s watch in 1775.

“Initially, the Haudenosaunee tried to maintain a neutral stance in the war between the patriots and the loyalists, but their proximity to the fighting and the urgings of the warring parties inevitably drew them in.”

Guy Johnson, a relative of William Johnson, marks the territory of four of the Six Nations in 1771 and he notes the territory to the north of the settled parts of New York still belongs to the Mohawks.

At this stage, the Mohawk people were settled into fortified villages Canajoharie and Fort Hunter, also known as the lower and upper castles, with Johnson Hall was conveniently situated in between them.

“There were colonial settlements all around and the Mohawks lives were closely connected with those of their colonial neighbours,” Hill said.

William Johnson died in 1774 and Guy Johnson took over as Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

“When armed rebellion broke out in 1775, he hoped to secure the allegiance of the Haudenosaunee to the British crown. This included making a journey to London with a party of Mohawk men to meet George III and the new colonial secretary, Lord George Germain,” explains Hill.

“A Haudenosaunee confederacy was broken by the American Revolution with the Oneida and Tuscarora peoples generally siding with the Americans, and the other nations aligning themselves with their traditional allies the British.”

Guy Johnson spent the war in New York leaving his brother-in-law John Johnson (William Johnson’s son), to take charge of the military campaign.

The revolutionary war was hugely divisive for the Haudenosaunee and relatively early on the Mohawks from Fort Hunter followed John Johnson to exile in Montreal where they continued to take part in raids against the Americans.

“In May 1779, George Washington ordered Major General John Sullivan to mount an expedition to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians with their associates and adherents the immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and to prevent their planting more.”

As a result of this campaign, 40 Haudenosaunee villages and all their crops and orchards were destroyed.

Thousands of refugees went west to Fort Niagara and spent a desperately cold and hungry winter there in 1780.

“Guy Johnson wrote in 1779 that about one-third of the Indian confederacy had lost their all and were camped around Niagara living on rations supplied by the British.”

When peace was negotiated between the US and the British, no mention was made of the Haudenosaunees land.

“Frederick Haldimand, the Governor of Quebec wrote to Lord North in London May 17, 1783 and said, ‘These Indians have great merit and sufferings to plead in the cause of Great Britain. It will be a difficult task after what has happened, they seem particularly hurt that no mention is made of them in the treaty. Actions not words can make impression on them, I have therefore dispatched Major Holland the Surveyor General of the Province of Lake Ontario to examine into the state of the old French post at Cataraqui and to survey the north side of the lake as I will endeavour to prevail on the Mohawks to settle there providing the country to be found propitious, there is a grant and John the Mohawk returned with him. Affairs with the Indians are in a very critical situation. I will consider as myself particularly fortunate if I can by the command which I am honoured by instrumental in alleviating the distress and in procuring the means of subsistence for men who have been of everything on account of their loyalty to the king.’

By 1784, it had been agreed that the Fort Hunter Mohawks would settle in the Bay of Quinte while the Tuscarora Mohawks and refugees from other Haudenosaunee nations would move to the Grand River.

Lands in the Bay of Quinte were purchased from the Mississauga people and 20 families arrived in what would become the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory on May 22, 1784.

The grant of 93,000 acres to the land to the Mohawks in the Bay of Quinte was confirmed by the Simcoe Deed of April 1, 1793 which mentions the grant as being in recompense for the losses of the Haudenosaunee and to reward their loyalty.

Government attitudes changed toward the Indigenous people over the course of the 19th century.

A copy of the presentation will be available library’s YouTube channel in due course.

National Indigenous History Month programming continues at the Prince Edward County Public Library through June. For details, visit peclibrary.org.

Filed Under: Arts & Culture • News from Everywhere Else

About the Author:

Interesting how this history does not include the Iroquois destruction of the Huron in 1649 who were living in southern ontario.