Cemetery walk inspires look at how 1832 cholera pandemic affected the County

Administrator | Feb 22, 2023 | Comments 2

By Sharon Harrison

Details of how people were affected by the cholera pandemic of 1832 showed several similarities to the COVID-19 pandemic some 191 years later. Interesting details began with a walk through Glenwood Cemetery in Prince Edward County last summer.

Sandra Latchford, president of the Prince Edward Historical Society, and president of Glenwood Cemetery, along with archivist Krista Richardson with County of Prince Edward Archives, shared details in a presentation on the weekend with about two dozen participants.

They also spoke to differences between the two pandemics, and how cholera arrived in Upper Canada, including Prince Edward County.

Cholera, a bacterial disease, which is usually spread through contaminated water, arrived in Quebec in June 1832, where it quickly spread through Lower Canada, then Upper Canada, including Montréal and Quebec City, as it became a pandemic.

Latchford notes the cholera pandemic of 1832 was the second in the cholera pandemic line of pandemics, adding “we are currently in the seventh right now internationally”.

The idea to research came to Latchford last summer when she was walking by a row of white headstones that had been moved to Glenwood Cemetery more than 70 years prior.

The idea to research came to Latchford last summer when she was walking by a row of white headstones that had been moved to Glenwood Cemetery more than 70 years prior.

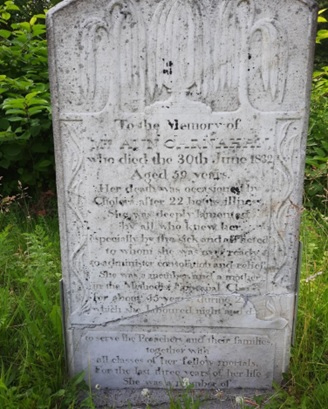

One for Ann Carnahan, a caregiver who died of cholera on June 30, 1832, caught her attention because it had a lot of writing on it.

One for Ann Carnahan, a caregiver who died of cholera on June 30, 1832, caught her attention because it had a lot of writing on it.

It read:

To the memory of Ann Carnahan who died the 30th June 1832 age 59 years.

Her death was occasioned by cholera after 22 hours illness. She was deeply lamented by all who knew her especially the sick and affected to whom she was every ready to administer consolation and relief. She was a member and a mother of the Methodist Episcopal church for about 45 years during 23 which she laboured night and day to serve the preachers and their families together will all classes of fellow mortals. For the last three years of her life, she was a member of the Canadian Wesleyans.

“I thought that was quite interesting that her story was depicted in this lovely monument,” expressed Latchford. “I really was struck about the intensity of the writing and the emotion and the detail, even telling that it took 22 hours for her to die after her first symptoms.”

The discovery of the headstone mentioning the cholera pandemic of 1832 led Latchford and Richardson to undertake some research, and to learn of the cholera pandemic’s impact on the County, as well as Upper and Lower Canada.

Latchford explains that when the headstones were moved to Glenwood, they were laid on the ground on the hill in Section N in the cemetery, the method she says that was used at that time.

“They did not put anything underneath them, not a concrete base or anything, and very slowly over time those headstones were sinking into the ground,” she explains, “They were being run over by lawnmowers, heavy equipment, and anything else that used the pathway.”

In 2014, Glenwood realized these stones were getting broken up, and many had lost their edges and were crumbling, so they decided they needed to preserve them. The stones were dug up and repaired by Hugh Heal, a local volunteer who works with old stones, where they were put in a line along Marsh Creek.

Most are not easy to read, according to Latchford. Her research revealed that headstones before 1845 or 1850 were more often personalized, containing more details because they were all hand done.

The Carnahan monument is marble which was a more expensive stone for them to have used, and it is believed to have been crafted by Gardiner Moore, a monument maker from Napanee who is known for his use of art deco elements, 100 years before art deco became popular, she explained.

“In the world of monuments, and these monuments of historians that search monuments, this monument is unique because it is from Gardiner Moore which they have not been able to find many examples of his monuments, but also because it survived.”

Latchford goes on to say monuments prior to 1850 are often just worn away; they fall over, are destroyed and are not preserved.

“They are very hard to find in Ontario these examples and his in particular,” she notes. “Not only did we get the information on cholera, but we got it on a really unique monument and that really is very interesting.”

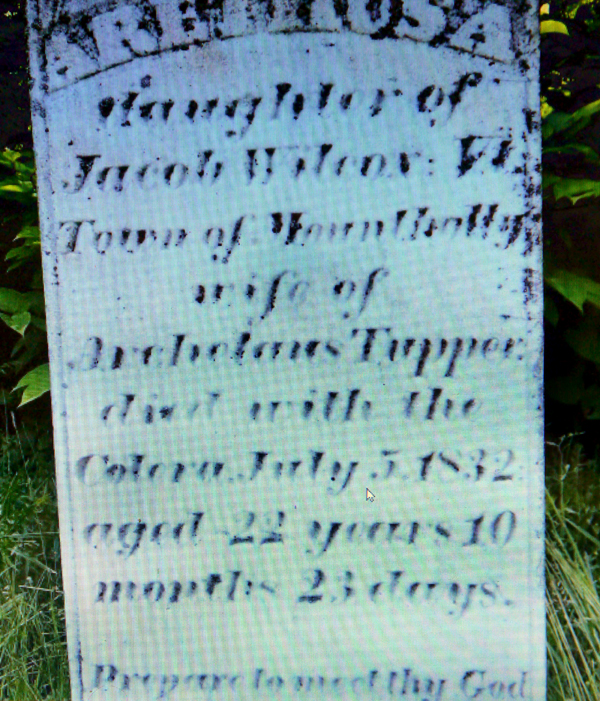

After Latchford found the Carnahan headstone, she went looking to see if she could find others, and she found one other right away, [note mis-spelling of cholera] that reads:

After Latchford found the Carnahan headstone, she went looking to see if she could find others, and she found one other right away, [note mis-spelling of cholera] that reads:

Arethusa, daughter of Jacob Wilcox the sixth, town of Mountholly, wife of Arehelaus Tupper, died with the colera July 5, 1832 age 22 years, 10 months and 23 days. Prepare to meet thy God.

While the wording is not quite as extensive as the Carnahan headstone, Latchford notes it doesn’t have the elements that would indicate it is a Gardiner Moore monument.

She indicates that she hasn’t found any other headstones that mention the cholera pandemic yet, but will be looking to find any other examples.

“Records of that time are scant when it comes to lots of details, but we have very hard proof that cholera was here at that time.”

In Krista Richardson’s detailed presentation, she too noted in her research that records and vital statistics were scant until 1861, officially. Any birth, marriage or death, if they weren’t parish records, were difficult to find.

In Krista Richardson’s detailed presentation, she too noted in her research that records and vital statistics were scant until 1861, officially. Any birth, marriage or death, if they weren’t parish records, were difficult to find.

While death notices or obituaries did exist often, she notes there was rarely mention of cause of death being noted as cholera.

“My hypothesis is that it was quite stigmatic and they didn’t want to put it out there.”

Symptoms of cholera can be absolutely none, mild to extremely severe causing death within a matter of hours, and include nausea, muscle spasms, cramps, vomiting.

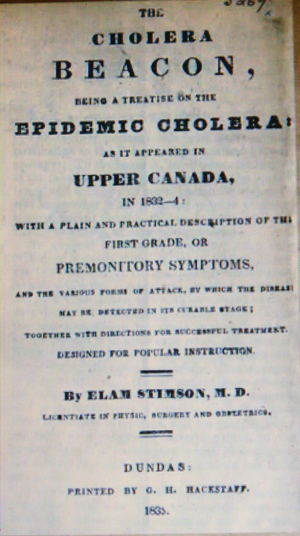

Richardson explained cholera was documented by the ancient Greeks, and also a class of it was documented originating in the Ganges Delta in 400 BC.

“It wasn’t a new disease or ailment, but this strain seemed to be much more harmful and violent than anything that had been documented before,” she said. “The severity of it and how it impacted the entire population was, and it became basically pandemic proportions by 1817.”

There are different types of cholera, including blue cholera, spasmodic cholera, Asiatic cholera, Indian cholera, and cholera morbus.

“One thing I did notice was that the different names for cholera did have a racist undertone, believing how it originated in the different communities and continents.”

She explained how blue cholera got its name from the blue tint the skin would have once the body was sickly and starved of oxygen and loss of fluids, whereas spasmodic cholera could be spasms or body spasms and also muscle cramping from dehydration.

“With Asiatic cholera, the disease first spread by travellers along fur trade routes, land and sea, to Russia in 1817, later to the rest of Europe and from Europe to north America and the rest of the world, hence the name Asiatic cholera.”

Indian Cholera, associated with the origin in India and the east, and as cholera arrived in India it was first spread through natives of the area, because they were in such close proximity where they lived, the lack of water treatment and lack of sewage, and the close living conditions.”

The term cholera morbus wasn’t used until the 1830s and it more or less meant deadly cholera, where it was noted a direct symptom was severe yellow diarrhea.

“There was quite a severe epidemic in Bangladesh in western India in 1817, as global trade began with shipping and travel to Asia, Russia, western Europe and the British Isles in 1831,” explained Richardson. “By February 1832, it was in London and in Bengal, India in southeast Asia the death toll was six figures high.”

She said, deaths in India between 1817 and 1860 in the first three pandemics in the 19th century were estimated to have exceeded 15 million.

“Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917; during the next three pandemics cholera deaths in the Russian empire during a similar time period exceeded two million.”

The spread began to be known as a product of industrial waste and urban poverty which was associated with the lower classes and less among the more wealthy and elite.

“We know that the newer immigrants coming to Upper Canada, a lot of them were living in shanty towns where there was no real sewage system, and in a time when sewage was mainly thrown in the streets.”

“We know that the newer immigrants coming to Upper Canada, a lot of them were living in shanty towns where there was no real sewage system, and in a time when sewage was mainly thrown in the streets.”

During the period in Upper Canada, people were still settling land into rural areas and urban areas were still growing, where small towns were also growing, although not as quickly as urbanized cities.”

Richardson noted how the conditions of the ships bringing immigrants to Canada from England, Ireland and other countries, depended a lot on wealth.

People were coming over to resettle and some of them were infected unknowingly, and that’s how they transmitted cholera to others.

“If we think of the small, cramped living conditions on the ships they come over on, it is no surprise that cholera spread like wildfire,” Richardson explained.

But because cholera was so widespread, nobody knew how it was transmitted.

“It was thought to be transmitted through the wind, but cholera is water-borne, which means it is transmitted when water is contaminated with cholera when feces are infected and when the bacteria is ingested.” She noted cholera can live in feces for 10 days.

“If you think about how much we do with water, contaminated or otherwise, it really makes sense, rinsing your vegetables, washing your hands, drinking water on a daily basis, and the sanitation systems and the sewer systems were so limited,” she said. “It was so common practice to throw waste in the street and, of course, that’s how the contaminated water supply began.”

She went on to say the Irish were particularly shunned arriving in Upper Canada, and highlights one of the most notable ships, the Carricks which arrived in Lower Canada in June 1832.

It was noted 42 passengers died on the Carricks and why a lot of times the Irish were not welcome because they were inadvertently blamed.

“After going over how cholera was transmitted, anyone could be infected, and in many cases not even know, but this particular ship was one of the most infamous for the infection rate and one of the most blamed for bringing it to Upper Canada as it was in Upper Canada and Lower Canada by that time.”

“Because of the blame, the Irish were not always welcome in town and cities, so they had to create their own shanty towns,” she explained. “This exacerbated the situation of cholera even worse because of the poverty and the deplorable conditions that they were living in allowed cholera itself to spread.”

A newspaper clipping from the Hallowell Free press indicates how people were in fear and that if they ever got sick they thought it was probably cholera, even when it was often something else, such as bilious fever.

Cholera sprung up in Prince Edward County in the summer of 1832, where the majority of cases were in Picton, something Richardson said made sense as it was an urban centre.

“By July 1, there were six cases, three of which died. By July 18, there were said to be 18 new cases,” described Richardson. “The doctors in Picton at the time went to consult physicians in Kingston to see how best to deal with the cholera situation.”

Latchford reiterated how record keeping was sparse and often inaccurate at the time.

“We were having a very hard time identifying how many people were affected and how many passed away from cholera,” said Latchford.

“We also have the same kind of emotional reaction to this pandemic, the fear that we had in COVID-19, anxiety and stigmatization that you wouldn’t want to necessarily tell people you have COVID or you had cholera, so sometimes they are not comfortable with that so there are some similarities to that across that time period.”

She said back in the day they also did quarantining, as well as hand washing.

“There were riots that reacted to the government doing quarantine in 1832. Some cholera hospitals were burned down because people did not want to have this pressure from government to interfere in this.”

She also notes how snake oil salesmen surfaced, advertising they had a cure purporting how folks wouldn’t get cholera if they took the offered elixir.

“The uncertainty of how it was being transmitted only added to the fear,” said Latchford. “It is borne in water, the drinking water and the contaminated by sewage which can happen in crowded conditions.

Another similar comparison to the current pandemic is that people who lived in the country felt more comfortable about the disease because they weren’t living in crowded conditions and could stay at home and avoid other people.

“They still they didn’t know how it was transmitted, so they could easily drink some water that tasted good, and didn’t smell of anything, yet get sick from it, so there was a lot of superstitious activity on how you might prevent this or deal with it.”

Latchford noted one difference is that the 2020 pandemic saw treatment and vaccines quickly, as opposed to 1832 cholera pandemic.

“It was about 25 to 30 years before they really had a good idea that the drinking water needed to be protected and started building municipal treatment facilities, and also dealing with the sewage and not just dumping it out your window in the street in a big city, you now had ways of transporting that away.”

Richardson noted, it wasn’t until 1854 that a doctor in London, England discovered it was water-borne disease.

“That’s why the London sewer system and the drinking water facilities that were starting to be built in the mid-1850s, and that’s a 25-year or more period, when they still had another outbreak, to totally pin down what was happening,” Latchford said.

She said, one of the morals of this story is that good clean drinking water is important.

“Our municipal systems are by law mandated to make sure we have clean drinking water, so we don’t get into the trouble with it again, and also with the treatment of sewage and making sure that is disposed in a sanitary and safe way.”

She explained why globally there have been seven pandemics, so far.

“The reason is that every time a country has an major earthquake, a hurricanes, flooding, fires, any disruption to municipal water supply and sewage treatment facilities, there is a risk of cholera raising its head.

“Generally, you’ll hear about it occurring in the refugee camps, and in Turkey right now it’s going to be at high risk for reoccurrence of an outbreak, where they are really scrambling to get enough water and keep the sanitation good.”

The headstones (57 in all) that Latchford noted had been transferred to Glenwood Cemetery, were from a local church in Picton in 1963 to free up space for a parking lot. She noted the bodies did not come too, just the headstones.

“The burial grounds were filling up, even in 1870, where Glenwood Cemetery coincidentally opened as a community cemetery [Glenwood opened in 1873] because the community leaders and people were worried there were going to be no local right-in-town burial grounds for the people,” Latchford explained.

One of the notes found in the records that piqued Latchford’s curiosity read, “We want to be ready for the next pandemic”.

“In 2020, the pandemic came to the County and an inscription on a 190-year-old gravestone makes a touching connection that we didn’t know.”

A recording of the presentation will be available shortly via glenwoodcemetery.ca, pecarchives.org, and pechistorical.ca

Filed Under: Featured Articles

About the Author:

Hugh Heal is a county treasure! I first met Hugh through a relative of mine, I had a family stone in Albury cemetery that was in ten pieces, many of which were sunken into the ground. Hugh expertly probed and found all of the pieces, then carefully marked the location and restored the stone perfectly complete with a period base. That was well over a decade ago. The stone still stands in place marking my great great grandfather Alyea’s grave site. I believe the true count of pioneer tombstones restored by Hugh is around the 1000 mark as not all were in Prince Edward County. Exceptional craftmanship!

Great article. Cemeteries are fascinating places. Children’s graves are always so poignant.

Kudos to Hugh Heal and his restoration efforts. I believe he has restored/repaired between 600 and 700 gravestones. Without his efforts, they would have been lost.