Pandemic-stressed food supply chain underscores security and resilience

Administrator | Jun 14, 2021 | Comments 0

Sprague Foods name derives from entrepreneurial founder, J. Grant Sprague (1867-1954), and the generations of Prince Edward County Sprague families that came before and after him. In 1925, Grant built the first cannery in Mountain View, naming it J.G. Sprague & Sons Canning Co., and the family has been canning in the Bay of Quinte region ever since. – Sprague Foods photo

By Sharon Harrison

Three local food experts spoke to food processing in a pandemic, sustainability, resilience and growing to feed a community during a recent virtual meeting of the Bay of Quinte Green Party of Ontario’s speaker series.

Host Albert Ponzo, executive chef at Picton’s Royal Hotel introduced Keenan Sprague, lawyer and fifth generation canner at Belleville’s Sprague Foods; John Thompson, County farmer and president of the Prince Edward County Federation of Agriculture, and Stephanie Laing, County farmer and co-owner and operator of Fiddlehead Farm.

Sprague has worked full-time in the family business since 2020, where he says he has the privilege of working with a lot of people whose parents, grandparents, and even great- grandparents worked at Sprague. He gave an overview of the food processing sector in Canada, and sustainability and climate change issues in the context of food processing and systems.

While Sprague Foods focuses on soup and beans now (all organic and grown by Canadian farmers), operations began in 1925 with tomatoes, peas and corn.

“At that time, everything was local and organic because pesticides were still decades away from being invented, so it was a very different world back then,” Sprague said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put the food industry in the midst of one of the most significant disruptions to the food system.

“The pandemic has really stressed our supplies in ways that people never foresaw,” he said. “Looking back, it seems we can understand why because for decades we have been building our logistics around this principle called ‘just in time’ which is meant to cut costs and deliver lower cost product to the consumer.”

Today sees a fragile system where the cascade effect is one piece of the supply chain affecting the next, and the next and implications are challenging.

“We are still having issues with supplies of ingredients and packing materials.”

He said the pandemic also underscored how food insecure Canadians are.

“When the pandemic hit, there were empty shelves in the grocery stores and there was a glut of food not being put through the normal restaurant channels because they were closed,” adding supply chains were not flexible and there were truckloads of food going to waste and people going hungry because there was not enough food in early months of the pandemic.

“I’m sorry to say, the Canadian food processing sector is in really bad shape,” and noted multi-national processors have preferred to open factories in the United States.

“We are actually losing jobs in food manufacturing, and it’s even worse than that because if you go to the facilities in Canada, they are way behind the U.S. in terms of capital upgrades and technology.“

“In my view, it’s gone way too far and we need to think about ways and policies that will help us restore and re-build our domestic food processing sector,” he said. “If bad things happen and we don’t have domestic manufacturing capabilities of food, it causes a lot of problems. If something worse were to come in the future and food scarcity became a bigger issue, we would certainly want to have some domestic capacity to make our own food.”

He said another contributing factor is a very consolidated grocery industry with a few companies dominating about 80 per cent of the market.

“That has created a real market imbalance where they are the gatekeepers to the market and there has been a lot of unethical practices where they treated suppliers with no regard of Canada’s wider interest of maintaining a healthy food processing eco-system,” he said. “It’s really been slash and burn and it’s a tragic story that has gone on for decades.”

Sprague said sustainability and food are synonymous, with a host of major problems in the way food is grown, as well as the way food is consumed.

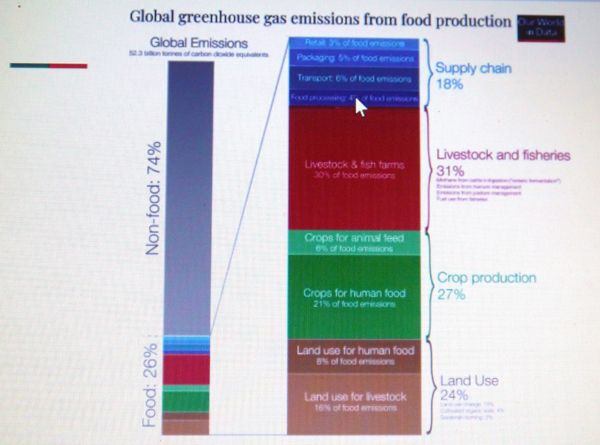

He noted 26 per cent of total global greenhouse gas emissions are from the food system, with only four per cent relating to food processing.

“We’ve got problems with pesticides disrupting eco-systems, the bee issue with colony collapse a few years ago, a big food waste issue, and then we’ve got packaging.”

Sprague said the majority of emissions occur before the product leaves the farm, where he said a majority relates to meat processing and is a significant contribution to emissions.

“Not all foods are the same and there is a big difference between plant and livestock animal emissions.”

More than half of all food produced in Canada is wasted, he stated, with the global average waste around 17 per cent and Canada sitting around 50 per cent.

As part of his research, Keenan said he learned Canada did not have a food policy until 2019.

“That’s remarkable to me, especially since it has such an impact on food security and climate change,” adding that as far as food processing goes, there hasn’t been a food champion in politics.

“The grocers have been advocating for the status quo because they like to buy their cheap food in Europe, the U.S. or Mexico, and the food processing sector is dominated by multi-nationals who want to locate in cheaper jurisdictions with lower wage costs.”

While consumers are addicted to cheap food, Keenan says there is a shift in behaviour as demand grows for sustainable, natural and organic products – a rise in consumption from 11 to 18 per cent in the last decade.

Keenan also addressed the plastics problem, noting a recent quote form Galen Weston, president of Loblaws, who said the plastic in oceans will soon outweigh fish, and that each person on the planet eats a credit card size worth of microplastics each week, and how the packing goods industry is responsible for a third of that.

Many cartons and pouches with many layers of synthetic materials, including plastics, end up in landfill despite indication on the packages that they can be recycled.

“We don’t have the facilities to recycle them, so they end up in landfills. There really ought to be some government intervention on that to inform the consumer.”

Sprague Foods prefers to use cans, but is unable to source a can that is 100 per cent made of recycled metal (currently, 40 per cent recycled materials), but Keenan adds the cans are infinitely recyclable.

“We have taken food for granted for many years in Canada, we have haven’t done enough to invest in our ability to add value from an economic or environmental perspective,” he said.

—

Fiddlehead Farm has been growing vegetables on 10 acres in Prince Edward County since 2012. It feeds members seasonally, with weekly bags in summer, monthly boxes in winter and bags every other week in spring. – Fiddlehead Farms photo

Stephanie Laing studied politics at Queen’s University before starting Fiddlehead Farm with her partner. They grow vegetables organically on 10 acres of land and are in their 10th year of production. Laing shared the story of the farm, including what they grow and why, and how they farm, and why.

Most of their production, about 90 per cent, goes to CSA (community supported agriculture) program, a subscription food box which subscribers can customize somewhat.

Laing says they feed at least 400 families over the course of one year.

Fiddlehead Farm grows some 50 different crops, including bok choy, lettuce, brassica greens, zucchini, basil, etc.

“It keeps us quite busy and we got into this through a combination of environmental issues and also a passion for food and we love cooking, which drives our passion for vegetables,” explains Laing.

“We wanted to build a farm that could be ecologically restored and could take a piece of fairly neglected marginalized land and turn it around into something that was highly productive.”

Laing describes how the farm they started was not the most fertile, where it took a lot of years to improve, one that has doubled the soil organic matter in that time.

“We are constantly working at trying to improve quality of land we are on, making it more productive, but also trying to ensure the eco-system around the farm can be supported or enhanced through our activities,” she said.

She said Fiddlehead wants to create full-time employment and operate as close to 12 months a year as possible.

“We facilitated that largely through doing a winter component to our food boxes, so we operate 12 months a year, distributing food every month and do that with a combination of root cellars, sweet potatoes, onions, garlic, carrots, beets and more which keep really well six to eight months in storage units.”

She says they are able to distribute that over the course of the winter months once the field season has wrapped-up.

“We are trying to fill that niche for people who want local food, food that is grown with care, to the nutrition, the fertility and the soil grown organically and as healthy as we can get it.”

“We are currently transiting to be lower dependence on tillage, to move as much as possible to be a non-till farm and largely with this type of farming, to make better use of the land.”

She said part of the reason they farm this way is because they didn’t see a future viable within the conventional food system, especially starting from nothing and being first generation farmers and having no farm experience.

“We are doing a lot of learning on the fly and we’ve had a lot of failures and successes.”

She talks about how their diversity of crops keeps them going, especially if one crop is not doing well due to pests or weather, for example.

“It gives us a lot of resilience to adapt to the climate challenges, same goes for hot dry years we tailor when and what we grow,” she says. “Doing a lot to use the environment we have, we are often asked if this scale and type of farm does it have a place in the farm future, the key lies in using small spaces where large equipment doesn’t do well.”

There is a place for this type of farming, she adds. “There is a lot of diversity and small farms add a lot of that resilience where we are able to adapt and switch, whereas some industries may find that more challenging.”

“We are quite nimble to adapting to shifting where we shifted in the pandemic from being 50 per cent farmers’ market to being 90 to 100 percent CSA and we were able to do that quite successfully and to survive, but that also exposed problems, such as the difficulty in finding employees.”

—

John Thompson

John Thompson is a third generation Prince Edward County farmer, dairying until 2001 when he switched over to producing organic broiler chickens, as well as field crops. He spoke to exposure to organic, supply management and regenerative agriculture.

He noted the higher retail cost of organic chicken is based on higher feed and other costs and acknowledged the product cannot contribute to food security for budget-challenged consumers.

“Supply management supports and promotes domestic production and contributes to the economy without the need for government subsidies,” said Thompson. “Having an orderly, planned system in which production is carefully calibrated to demand ensures that farmers and consumers are not subject to the boom and bust cycles which characterize the pre-supply management era,” Thompson said.

Canada places a cap on the amount of dairy and poultry products which can be imported duty-free.

“Behind this base amount, effective tariffs are used to ensure that the import levels are predictable and can be factored into production planning.”

Canada is one of largest per capita chicken importers in the world, where Thompson noted farmers do not set wholesale or retail prices.

In terms of benefits, he said supply management ensures Canadian consumers have access to high-quality, domestic-produced safe dairy and poultry products that are among the least expensive in the world.

“It also provides significant economic benefits to an extensive domestic supply chain from feed producers to processors,“ he said. “It also allows farmers to be self-sufficient and profitable.”

Addressing regenerative agriculture, he said there is no specific definition, but there is a checklist of regenerative practices.

“We use our 200 acres of prime land to grow a three-crop rotation of corn, beans (either soy beans or black beans), winter wheat followed by a cover crop,” explained Thompson. “The wheat is harvested in late July and the wheat straw is baled for use as bedding for the chickens.”

He said the manure from the chicken barn is spread on the wheat stubble as a base fertilizer for the following corn crop.

“This provides enough phosphorous and pot ash to provide carry over for the next two crops as the bale straw returns to the soil.”

“After spreading the manure, we spread cover crop seed, currently oats, and incorporate it into the soil to reduce the emissions and allow the cover crop to germinate.”

He said the top growth produces carbon dioxide while the roots sequester carbon to support soil health and life.

“Cover crops also stabilize the soil for protection from erosion by wind and water. Combined with no-tillage planting with the corn, beans and wheat, this rotation is our regenerative agriculture practice.”

He said by putting carbon back into the ground, it both removes it from the atmosphere, helping the climate, and improves soil health.

“Cover crops, nutrient management and reduced tillage are key to increasing the amount of carbon stored in the soil.”

“Restoring soil faster than nature makes it can help address the fundamental challenges of water, energy and climate,” he said. “The positive effect of no-till and carbon sequestration is dependent upon residue retention, cover cropping and crop rotation.”

He noted how ruminant animals (herbivores such as cattle, sheep, goats etc) are especially beneficial since a portion of their diets comes from perennial forages, which are superior to annual crops.

He said ruminant animals get a bad press because of their methane emissions, as well as greenhouse gas. He said they play an important part in the food eco- system as they digest forages which human and single stomach animals cannot, and produce highly nutritious milk.

“However, methane is short-lived, changing to carbon dioxide and water and converted to oxygen. The steady ruminant population would result in a steady amount of methane as the breakdown would equal the new emissions.”

Although estimates vary, he states agriculture is responsible for around 15 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Filed Under: Featured Articles

About the Author: